Save the Last Waltz for Sonny Boy

by Jim Kelton

From Blues Revue magazine, issue no. 72, Nov 2001. Copyright © 2001, Straight Up Inc.

|

Whatever ended with the Last Waltz started with the blues.

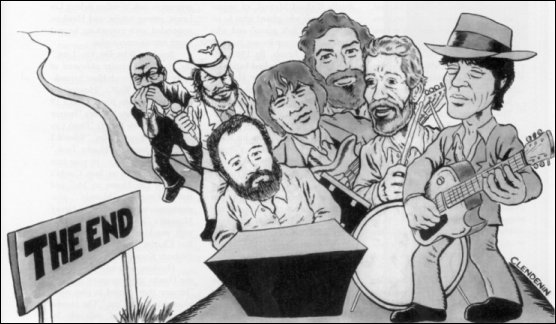

Twenty-five years ago on Thanksgiving Day 1976 in San Francisco, The Band presented a farewell appearance at an old arena known as Winterland that included some of the most famous names in rock, became a famous album, and yielded a movie that outclassed everything else in its field.

Directed by Martin Scorsese, shot in Panavision and starring - in addition to The Band - Ronnie Hawkins, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Dr. John, Eric Clapton, Muddy Waters, Paul Butterfield, Van Morrison, Emmylou Harris, the Staple Singers, and Bob Dylan, the event was an insightful, well-rehearsed coming together of the seminal forces that had contributed to rock in the previous three decades.

It represented a formidable justification of the music that had become the popular music of the day and more, the music that constituted a populist revolt against the big bands and their swinging offspring who dominated the recording industry (country music excepted) until the birth of rock 'n' roll. It was a birth that a lot of people must have thought occurred in the dark, since nobody had seen it happen.

But the simple truth is that there never was anything quite like the Last Waltz again. The variety, the enthusiasm, and the unceremoniously positive energy that dominated the whole affair just weren't there after that. Neither were the communities that nurtured them.

The Band came up through a traditional circuit of dance halls, barrooms, roadhouses, private parties, and off-the-frayed-cuff recording sessions that no longer existed in 1976. "The old neighborhood," as Robbie Robertson said in one of his songs, wasn't even there anymore. The group was famous for backing Dylan when he established the contours of folkrock during his 1965-66 tour, but its roots as the Hawks were far deeper than that. As a unit, The Band came out of a down-home heritage that, compared to the pumped-up contrivance that became The Rock Industry, was as vital, exotic, and mysterious as a voodoo ritual.

Levon Helm, the drummer, grew up in Marvell, Ark., the childhood home of Robert Lockwood Jr. (stepson, virtually everyone agrees, of Robert Johnson, whose compactly sinister spiritual precepts - hellhounds, crossroads, lust, betrayal, and eternal damnation - encapsulated blues lore as thoroughly as Elvis' hillbilly irreverence later focused attention on the darker side of the Grand Ole Opry's whiskeydrinking, mother-loving, haw-hawhawing attitude). Helm listened daily to Sonny Boy Williamson II's live King Biscuit Time blues broadcasts from radio station KFFA in Helena, which was only a few miles away.

Helm, who reputedly performed as a young guitarist in a band known as the Jungle Bush Beaters, eventually attracted the attention of rockabilly legend Ronnie Hawkins, who had two hits behind him at the start of the '60s: "Mary Lou" and "Forty Days," the first a bombastically humorous ballad and the second a twofisted takeoff on Chuck Berry's "Thirty Days."

But Hawkins' buildup as a rising star, which included an appearance on Ed Sullivan's TV show, was behind him. The group that accompanied him on his hits, including pianist Will "Pop" Jones and guitarist Jimmy Ray Paulman, had dissolved. Hawkins was putting together a new act in an effort to survive a musical era that had deteriorated into the kind of bland pop championed by Dick Clark and Hollywood (represented by Frankie Avalon, for example, and dozens more - the Technicolor Elvis and the dewy-eyed teddy bears massproduced to capitalize on his marketable eccentricities). The British Invasion, which included its own share of carefully manufactured matinee idols, was still a few years away.

So Helm and Hawkins together started recruiting a more soulful crew. At first, there were guitarist Robbie Robertson and bassist Rick Danko, both Canadians, who gravitated to rock 'n' roll in or around Toronto. Later came Garth Hudson, master of the Hammond B-3 organ (whom Hawkins swore he hired after hearing him play in a mortuary), and finally Richard Manuel, an impassioned singer who played what he referred to as "folk piano" and who came out of a group known prophetically as the Revols. By 1962, the Hawks were a full-fledged band that included a saxophonist Hawkins nicknamed "the Arabian Fabian."

Hawkins was nothing if not a wildly outrageous rock 'n' roll throwback. He spoke a brand of hillbilly patois that translated into his music as aggressive irony. But, more importantly, he had grown up in northwest Arkansas listening covertly to the blues. He was introduced to that music in a segregated black ghetto in Fayetteville known unapologetically as "Nigger Holler," and he gained entry into the social milieu that thrived there through Buddy Hayes, who shined shoes at a barbershop where Hawkins' father cut hair.

Hawkins also was a country boy from the Ozark Mountains who had spent his early childhood in nearby Madison County, an impoverished sector of flinthill farmland that had a reputation for being a rough, feudal enclave given to blood vendettas and fiercely rugged individualism.

Together, that combination of hardboiled country sentiment (people in Madison County didn't sing "Wildwood Flower" the way Joan Baez did) and down-and-dirty Saturday-night blues proved to be a productive and progressive style for Hawkins and his Hawks. It led directly to their most powerful performance together: a version of Bo Diddley's "Who Do You Love" that, when played live, featured massively distorted, sexually insinuating guitar by Robertson and an apoplectic vocal by Hawkins that communicated primal ferocity to the bareknuckles crowds he attracted.

The customers - "drunks, whores, and flakes," as Hudson once described them - went wild for the salty innuendoes and raucous irreverence of Hawkins' flamboyant style, one that owed much to such firstgeneration rock 'n' rollers as Jerry Lee Lewis, among others, and Hawkins responded with everything he was worth entertainmentwise.

Besides "Who Do You Love," the Hawks' repertoire consisted of cover versions of such blues haymakers as Howlin' Wolf's "Howlin' for My Baby," Muddy Waters' "She's 19 Years Old," T Bone Walker's "Stormy Monday," Bobby Bland's "Don't Cry No More," Ray Charles' "What'd I Say," Bill Doggett's "Honky Tonk," and such typically inyour-face jazz/soul routines as Sam Cooke's "Bring It On Home to Me" and Bobby Timmons' "Moanin'," plus unprepossessing rarities like Henry Mancini's "Peter Gunn" (delivered with machine-gun precision) and Ray Charles' obscure "Hard Times (Nobody Knows Better Than I)."

Hawkins once said that he and the Hawks split company in 1963 "because they wanted to play more blues than I'd let 'em." The Hawks' account, articulated concisely by Robertson, was that Hawkins inhibited the group from performing its original numbers.

To be fair, there's probably an element of truth to both sides of that issue. But the fact remains that Hawkins' brand of rockabilly, a direct descendant of previously taboo blues mixed with country rebelliousness, was both profoundly unique and uncommonly challenging: Hawkins' "shows" frequently started at noon and ended at midnight.

It was a rowdy scene, geared to hardcore partying, and it was based solidly on the blues.

Helm, who developed into what super-instrumentalist Mark O'Connor described as "the best country singer alive," was enthralled with the blues. He led the vocals on the Hawks' versions of "She's 19 Years Old," "Howlin' for My Baby," "What'd I Say," and "Hard Times."

Robertson, whose ferocious guitar solos reflected his admiration for the intricate wail of Wolf's ace sideman, Hubert Sumlin, specialized early on in dissonant blues effects filled with dynamic rhythmic undercurrents made expressly for dancing, drinking, and letting off steam.

At the center of this, Danko's Chicago/Motown/Delta bass playing fell into place naturally as a kind of amalgamation of the stylistic diversity that was coming together in the Hawks' music.

So what the Hawks were doing through their soulful intensity was extending a tradition that predated the recording era. They were part of the evolution of Southern music that grew out of hoedowns and field hollers, juke joints and cotton-country barbecues, minstrelsy, sentiment, and richness of expression. Lyricism - the language of emotion - is at the heart of the South's music as well as its literature. It constitutes a poetic tradition that is instinctually contradictory- raw and gallant, funny and charming, narratively compelling and mystically insoluble.

My view of rock 'n' roll's initial assertion came directly out of my experience with the Grand Ole Opry and Pentecostal churches. That was followed almost immediately by exposure to rock'n' roll radio and Hawkins and the Hawks laboring dramatically through their day-long jams and hustles at the Rockwood Club just outside Fayetteville where I grew up.

To be present later at the Last Waltz - the career-commemorating performance by the first all-pro homegrown rock 'n' roll band I ever saw make it big - was a mixed blessing.

Rock 'n' roll was not ending that night beneath the mirror-ball pretension of hired dancers sashaying to the campy strains of the Berkeley Promenade Orchestra. The blues weren't dying because Clapton and Butterfield and Muddy Waters (who, accompanied by Bob Margolin, stole the show with "Mannish Boy") were participating in some grand gesture of triumphant perseverance. Southern lyricism was not disappearing in the syncopated performance of "Caravan" by Van Morrison or in the subtle alliterations of Joni Mitchell's "Coyote" or the sappy sadness of Neil Young's "Helpless." Dr. John's "Such a Night" was not a swan song for New Orleans rhythm and blues. There was not even any real finality to Hawkins' performance of "Who Do You Love" or Dylan's heavily conceived take on "Baby Let Me Follow You Down."

Dylan once referred to rockabilly (the music the Hawks signified when they were apprenticed to Hawkins) as "the backbeat of America."

That's what was on the line at the Last Waltz - the spirit of a genuine heritage drawn from the experiences of the millions who built the levees, cropped the shares, fished the rivers, and whooped and got drunk on Saturday nights to celebrate.

Somewhere in the distance that night 25 years ago - maybe during Helm's almost-perfect singing of "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down" or in the riddles of "Up On Cripple Creek" - the Last Waltz summoned up one last time the sound of America on the mend, being rebuilt during Reconstruction, changing its face in the terrible aftermath of bloodwon Union. Somewhere there you could hear Sonny Boy Williamson laughing, and you could feel the resentful backlash down in Fayetteville's "Holler," where people knew the truth:

Miracles truly do occur.

"Moanin' " is a universal condition.

"Stormy Monday" is more than a metaphor.

And "Who Do You Love" is a timeless and unanswerable question.