Rick Danko - The Last Interview

by Robert L. Doerschuk

This interview was done on December 7, 1999, 3 days before Rick Danko's death. Copied from the All-Music Guide. The text is copyrighted. Please do not copy or redistribute.

|

So it was on December 7 at the Ark, the legendary venue in Ann Arbor, Michigan, as Danko gave what would be his final performance, just three days before he would die peacefully, in his sleep, at his home near Woodstock. Only about a third of the intimate space was filled, with a mix of graybeards and younger fans, as Danko lumbered out and settled onto a stool at the front of the stage. In a word, he looked terrible: He was critically overweight, and within minutes was perspiring noticeably. Someone had put some water on the floor next to the stool; it took Danko a few long moments of stooping and sweating before he could lay a hand on the bottle. As he straightened back up, he spilled some of its contents on his jacket and pants. At one point, he even had to stop the show and, with apologies, leave the stage for a few minutes to catch his breath backstage.

For maybe an hour he sang, accompanied by his longtime pianist and accordionist Aaron Hurwitz. His voice was rougher than on the old records, and noticeably lower. In playing some of the tunes he had helped immortalize years before -- "Chest Fever," "Shape I'm In," "Stage Fright" -- he pinched on many of the high notes which he had picked off cleanly and clearly years before. But there were moments when he locked onto a lyric, or made those magical leaps up half an octave where you least expected it in a melody, that stirred memories from a time when Danko and his colleagues in the Band were at their prime -- when they were virtually the only act playing for young audiences in the '60s that didn't flounce like superstars or turn their backs on unhip aspects of Americana tradition.

Back then, nobody sounded remotely like Rick and his Bandmates. Levon Helm's raw, drawling vocals and deadened thumping drums, Richard Manuel's impossibly gossamer falsetto, Robbie Robertson's pioneering adaptations of narrative folk balladry, and Garth Hudson's unique and still unmatched mastery of keyboard textures, with Danko's own unobtrusive grooves on the bass and heartbreaking expressiveness as a singer: It was a unique combination of ill-fitted yet perfect attributes. And where less worthy ensembles labored to convince audiences that psychedelic excess could substitute for musical substance, the Band kept its production budgets low and let the music speak for itself.

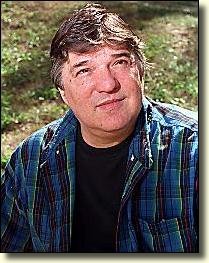

Images and echoes of the Band adorn the scrapbook of our time: Epochal tours with Bob Dylan, the ramshackle eloquence of Music from Big Pink, the graceful benediction of The Last Waltz. And those photos of the five guys, looking like Confederate hoboes standing on Cemetery Ridge with the Pennsylvania countryside fanning behind them into the mist, or huddled around a dusty old piano and trad jazz drums in a cramped basement. There, thin, sleekly handsome with his black mustache and maybe a bowler hat, stands Rick Danko, already seasoned by years of teenaged touring with Ronnie Hawkins yet still young.

The years that followed would bring a mixture of joy and pain for Danko. He would lock horns with Robertson over questions of who wrote exactly what in the Band's repertoire. In 1968, he would sustain nearly crippling injuries in an automobile accident, with complications that bedeviled him for the rest of his life. And in 1997, he would beat a serious drug rap in Japan, where customs officials caught him with four-hundredths of an ounce of heroin. Danko, in handcuffs, promised to stay clean; the judge suspended his sentence, citing specifically the defendant's contribution to the world of music and his work for charities and other good causes.

When we met him a few hours before his show at the Ark, Danko was moving slowly. He edged ponderously between a tiny table by the window and a refrigerator by the door, then sank into a seat by my tape recorder. We were a long way from the private jets that once whisked the Band on its tours, but it didn't seem to bother him at all. "The great thing about this is, like, a bus is very big," he explains, breathing a little heavily. "It requires more concentration. This doesn't have the bunks in the back, but it does have a great floor plan. For two or three people, it's perfect. Four people, tops. That's kind of how we deal with it. When we need a band bus, I just put a band on the bus."

He and Hurwitz and their driver were wrapping up a Midwestern tour. They had played five straight gigs before arriving in Chicago the night before; rather than rest, Danko insisted on getting together with friends and jamming for a few hours. The pace was taking its toll. In his RV, he smoked a series of cigarettes in quick succession. Several times during our interview, he would stop and ask me to adjust the thermostat, first cranking it up to 80 degrees, then down into the 60s. His speaking voice was raspy, his complexion sallow.

But later that night, after wrapping up his show, Danko beamed happily as he mingled with his small audience. "You know, I'm selling my new CD here," he had told the room after the final number. "It's called Live on Breeze Hill, and I really hope you buy a copy. We've tried to be environmentally conscious about it; we've even used a soybean-based ink for the jacket -- which is cool, because I can eat whatever I don't sell."

Danko laughed, then his face softened into a kind of wistful smile. "But, you know, if you don't want to buy the CD, that's OK. Just come on up, and we can talk a little bit anyway."

Before we left, I took my wife up to meet Danko. He broke into a wide grin, his eyebrows arching with delight. "Ah!" he exclaimed, and he bent forward, in a tiny bow, as he took and kissed her hand.

![[Rick Danko - The Last Interview]](../band_pictures/amg_120799_1.gif)

The Early Years

What are your recollections of Ontario?Well, you know, I grew up in a rural kind of setting. I was six miles from Simcoe and six miles from Delhi, and ten miles from Turkey Point. We had three stores, a couple of fruit stands, and a juke box. My greatest memory, of course, was harvest time, when all the fruit and food on the vine was the best. And all the great harvest parties. It was in the tobacco belt, where I really grew up. I was allergic, though, to gardens. I didn't like sand under my fingernails or toenails. I'd start sneezing whenever that happened.

When did you know that you would be a musician?

I was very young. Five or six years old.

How did you get into playing music?

My father took me out to some weddings, where he was playing in front of people.

He was a musician?

Yeah. He played all stringed instruments.

In fact, you made your debut performance in your first-grade class.

Yeah. I sang a couple of Lefty Frizzell songs, I think "Mom and Dad's Waltz." Might have done "Long Black Veil" as well, by Lefty Frizzell, when I was five years old.

Did the other kids in the class enjoy your performance?

Well, it was for the parents, you know. I was sharp enough to know that I was a sickly kid, and the lyrics of a powerful song, if you're listening to Hank Williams . . . I remember the teacher said, "If anybody has any problems [in the performance], don't panic. Just don't stop. Just do something." Now, I had arranged a tune called "Little Brown Jug." I didn't read music, but I just knew that it was "one-two-three-four, change; one-two-three-four, change; one-two-three-four, change." That's how the song went. And somebody, sure enough, fucked up. I was playing the lead, the melody. And my oldest brother and this girl Joyce, who was in grade eigh -- I was seven years old, actually, my birthday being December 29; they were playing the rhythm. Somebody miscounted, so I stopped playing and I pretended I was going to hit them over the head with my banjo. I flicked the bridge down to make a snapping noise, and it scared everybody. That was my first exposure to comedy, I'm sure, because I dealt with it on a comedic level.

Then at the end of the night, we all got up onstage to sing in a choir-like setting. I got to feeling sick; I felt an anxiety attack coming on. It was an interesting night, to say the least. From that point on, I started doing every Christmas concert. Then I started playing in my schoolteacher's band, before grade seven, I guess it was. Herb Tittnuss was his name.

Reportedly you played with accordion bands a bit in those days.

I knew this guy who played accordion; he could play in any language. Marcel Gorse was his name. He was just great, he was phenomenally great. He exposed me to songs like "Begin the Beguine," songs that had more than three chords. Great, great European stuff. And I had three aunts who sang big-band songs, which turned me on to harmonies. They would do, like, the McGuire Sisters, that kind of thing: "Sentimental Journey," jive music, you know? So I had a lot of exposure to a vast array of music, from big-band songs to singing voices to country music, my biggest influence. Some of those country ladies were the greatest, like Kitty Wells and Patsy Cline and Mother Maybelle.

Then it was a couple of years until I got to high school. I knew I had no foundation for algebra because I had fucked off so much in public school. So Herb Tittnuss had to go back to teacher's school to get the rest of his degrees. He wanted me to go and become a typewriter repairman or something, but I opted for a job cutting meat. I became a meat cutter.

Why?

Well, the meat-cutting thing, I was a very proud, country kind of person. I didn't want to do what other people did who quit school, and that was to mooch off the parents.

But you were playing music around town at the same time.

Yeah. I have an uncle named Rollie, who delivered groceries from a warehouse to grocery stores. And I would . . . get in there and paint posters to put up in the stores where he would deliver groceries. That was my form of advertisement. Usually, in that rural setting, it was the only show in town, especially in the wintertime.

Voices in the Air

What role did radio play for you as you were growing up way out in the country?Well, it was a great escape, like television eventually became. I remember when my father got our first television; it was a 21-inch black-and-white television -- one of the greatest escapes of all time. I was kind of a sickly kid; I had asthma, and I was hyperactive, so they had me on . . .

Was it Ritalin?

I was a little before Ritalin; that was later on. That came in the late '50s. The late '40s, I think they put you on antidepressants. But Hank Williams, country music, Sam Cooke, rhythm and blues, Little Richard, Fats Domino . . .

Were there any disc jockeys who made an impression on you too?

Wolfman Jack. He was in Del Rio and Laredo, Texas, in the late '40s. There was a guy named the Hound who had a great show out of Buffalo; it was just incredible.

Knowing what radio used to be, what do you think of it today?

Well, you know, in the past ten days we've done about three radio shows that go out to maybe 400 stations. That's very special, to be able to reach that many people. We played, I think, four radio shows, and we did five live gigs. The five live gigs, they're special.

But does the radio mean something different to listeners today than it did when you were growing up?

I'm sure that that's always gonna be the case. But it does mean something, and that's the thread that connects all of this. Time changes, you know. Life goes on. Fads are fads. But the good stuff lasts forever. Nothing stays the same. That would be very boring if it did.

Woodshedding with Ronnie Hawkins

When did you first see Ronnie Hawkins onstage?I saw him play with Conway Twitty in 1959, I guess. Ronnie was like an animal onstage, you know? I was just in awe. So I booked myself to be his opening act on five shows in 1960.

Where was that?

In Port Dover, at Summer's Point. Don Ivey, who was a great old man, he used to book big bands on the lakeboats that would go from Erie, Pennsylvania, to Port Dover.

You booked yourself to open for Ronnie specifically because you wanted to join his band?

I don't know. It didn't really dawn on me what I wanted at that point, you know? I had my own band, but he hired me to go to Summer's Point and play rhythm guitar, although I wasn't really a rhythm guitar player. It was a dream come true. I mean, beach girls and everything a country boy could imagine [chuckles]. So I learned to play bass while I was there with Ronnie; by September, I'd started playing bass.

Were your parents doubtful about their son hitting the road that young?

Well, being the sickly kid that I was, I was able to manipulate my parents to let me do just about anything that I wanted to do. They were great, you know. They were really behind any of my choices or moods.

Was it hard to tour with an act like Ronnie Hawkins at age 17?

God, no! I mean, great weekend parties!

But Richard Manuel compared working with Ronnie to going through boot camp.

Well, Ronnie was the closest front to a type of discipline that we would have gotten, the way we were going.

When you left the group, reportedly it was because of an argument over your decision to bring a girlfriend to one of the gigs.

It was silly. He was supposed to go to New York, and he missed his plane or something, and he came back into the club. A girlfriend had come into the club, and he was gonna fine me $50.

Why?

Well, he had this thing about socializing, you know, and bringing in customers. But that's not what life was about, really. Four months later, he said, "You haven't paid me the money yet." I said to him, "Well, I wasn't planning on it. Go fuck yourself." When he fired me, he'd really gotten drunk. We were having a party, and Conway Twitty was there. And it got out of hand because of the emotions. It was time to leave anyway; it was time to do something else. So I got Levon to fly in before the night was out, and we started playing as Levon and the Hawks. But we're all good friends; it's just another road story.

Birth of the Band

|

Well, rockabilly was the big thing with Ronnie Hawkins. I didn't much know about that. But Ronnie was sharper than most people would give him credit for. He sensed the change stronger than anybody. That's why he did what he did by putting a group like the Band together.

Wasn't he thinking of you as his backup rockabilly band, though?

No, he was thinking of shaping some destiny. That's why Richard Manuel was their lead singer. I was singing, Levon was singing. He was treading deeper waters. I mean, rockabilly was kind of on its way out. Levon and I both come from a rural setting, much the same. Our fathers were farmers, and we were shaped by country and western music. It was [Albert Grossman's secretary] Mary Martin who brought me into Bob Dylan with Highway 61 Revisited.

You hadn't heard Dylan before that album?

No. There were two songs on that: "Knoxville Girl" and "Don't Think Twice, It's All Right." Those two songs killed me. They just grabbed me, grabbed my ear. But when I turned the Band onto Bob Dylan, we were going through a jazz period: Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, Mose Allison, stuff like that. I'm sure Levon didn't like that song "Mrs. Jones" too much.

"Mrs. Jones"?

You know, "something's really happening but you don't know what it is, do you, Mrs. Jones?" [i.e., "Mister Jones," from Dylan's "Positively 4th Street."]

The Big Pink Sessions

As you heard Dylan for the first time, did you sense that you could actually work with him as a musician?Well, we did. Music from Big Pink came up. Robbie and Bob would come to Big Pink. Richard, Garth, and myself lived there for about a year. Robbie and Bob would come every day to Big Pink for seven or eight months, and we'd work together every day.

You're the guy who actually found that house.

Right. I went up to work with Tiny Tim and Richard Manuel; we all worked together on Bob's movie, Eat the Document. The restaurant where we ate, the woman's husband died. They were from Long Island, and she didn't want to stay there after he died. So she went back to Long Island, and that's how we got the house. It was, like, a three-bedroom house for less than $300 a month. Bob had us on a small retainer, and we got to live like kings. We bought a '47 Oldsmobile and a '49 Hudson.

You put a unique sound together at that place.

Oh, yeah. It's funny. People were stacking Marshalls, and we were trying to get a balance -- acoustically, you know?

How much of the process of defining that sound was premeditated? How much came from just jamming?

All of that, you know? We were just experimenting. We were trying to get a balance. You know, the Band's first album was recorded on four-track. The second album was eight-track, third album was 16-track, fourth album was multiple tracks. Now it's digitally done and computerized.

Even with 32 tracks, did you cut everything live, or did you overdub many of your parts?

All of the above. You gotta understand: Good things never get planned, you know? You just live your life and you do the best that you can. We didn't sit around, thinking that this was great or this wasn't great. That didn't happen. We just did what we were doing. To this day, we do what you do. You survive, you know?

The deliberate low-tech aspect of the Band's sound . . .

I call that an economic equation: Less is more.

But, for example, you could have recorded on a Steinway grand instead of a funky old upright piano.

And in some cases we did! I can't think of the name of the piano . . . it was a Bösendorfer! $75,000, you know? That's what a Bösendorfer goes for, a good one.

Did Levon ever talk about livening up the drum sound, instead of sticking with that unfashionably dry production?

All of the above! We did as much experimenting as you could imagine. Sometimes our soundchecks were longer than the performances themselves.

The Band's image, like its music, was almost deliberately archaic.

Kind of reminds me of Grandpa Jones, you know? He grew into how he looked. I met him when he was, like, in his 30s. I was five years old, and he put all that makeup on.

Living Like Rock Stars

You toured with Dylan at one point on a private jet. How did it affect the Band to suddenly be operating at that level of superstar privilege?Well, first, that plane wasn't really a jet. The first plane, we called it the Volkswagen of the Sky. It was called a Lodestar. Peter, Paul and Mary had one, and Bob had one. It would do about 130 miles an hour and take 24 hours to get to California. A month later, everybody bailed; that was the end of that. The Band got into jets when we started having some success. We got into a turboprop -- an Aero Commander, it was, with the wings that sloped forward. It could go 500 miles and be home in an hour and a half each night. That was a jet that had two bedrooms. I remember that [photographer] Barry Feinstein was married to the chick with the big tits who was on the Johnny Carson show. . . .

Carol Wayne?

Yeah, she was a good friend of ours. And Johnny Carson was asking her about the jet. He heard that it had a fireplace, from one of the band members. She said yes. He said, "Well . . . does it work?" [Laughs.] But that was one of the greatest tours in the history of the Band. We were one of the first groups to go out and gross $60 million in 40 days; now they do that in two weeks. We got exposed to wine that costs $500 a bottle.

Does wine that's that expensive taste that expensive?

You're damn straight [laughs]. I have favorite wines, but the best drinkable wine would be Lafite Rothschild: '67 was my favorite year. It would be a little too fruity for wine connoisseurs, but that was a great wine. Any wine that I've had that they've said is great has been great. It doesn't get you drunk; it gets you high.

Do you miss all those high-roller perks?

I remember the best part of it all was raising my family. It's the stuff that anybody . . . you know, it's the stuff that lasts. The flash-in-the-night way of life isn't real. It's nice. Everybody should go through it. I mean, there were times when . . . But the best part, you know, is growing gracefully with your family. The American dream is that there's a pie out there that should be big enough for everybody. You cut it up, and if you don't get to do that, you sure are missing out on a lot in life. I've had the pleasure of enjoying the company of certain teams that I've put together that feel that way. That's what keeps me in it.

Did the success enjoyed by the Band get in the way of its creativity?

Absolutely.

What was that all about?

Well, you know, you're gonna have to wait for the book [laughs]. It'll cost you money for that information.

The point is that success breeds a different kind of energy than the pursuit of success.

Absolutely. And that applies to drugs, that applies to health food, that applies to relationships. It's all in there somewhere.

Garth, Levin . . . & Mae West

The Band was such a unique combination of artists. Setting aside personal issues and speaking just as a musician, what's your view on the contribution of, say, Garth Hudson to its sound?There's only one Garth. I mean, he'll be with me 'til my dying day. You know, it took us six months to save up enough money to buy the Lowrey organ.

The Band bought his Lowrey organ for him?

Well, we all saved up for it, because it cost five or six grand; nobody had that in them days. When we got the organ . . . I hope this doesn't offend him, but Garth may suffer from a little form of narcolepsy. But when we got the Lowrey organ, I mean, it had string sounds that would just put goosebumps on your back -- chicken skin, you know? We'd be doing "The Weight" or some song, and he'd look up and he'd say, "Rick? Now?" Then he'd bring the horns in, and the strings. "Now, Rick?" [Laughs.]

No other keyboard player, to this day, has approximated Garth's sound.

Well, it was great. It just made everything big, you know? More orchestral.

And more emotional.

Yeah. I once asked Garth about getting away with what he gets away with. And his reply was that he used to play at his uncle's funeral parlor. He'd just listen to the eulogy. And when it was time to push the buttons that made people cry, he would push those buttons [laughs]. That's the thing about Garth: He really plays the song, whether it be a eulogy or whatever.

What does Levon Helm mean to you as a musician?

He has one of those voices that heals people; he's a great healer. And once again, there's only one Levon. We have a great chemistry.

Did you find it easy to set up a bass-and-drum groove with him?

Well, he's one of the best. We played together for 39 years, so we have a chemistry of being economically capable of setting that feeling up, whether it's a punch in the stomach or a slap on the back.

And Richard Manuel?

One of the greatest singers of all time. You know, Robbie [Robbie Robertson] as a songwriter . . . a great songwriter. He's been writing songs since he was five, you know? The nucleus was phenomenal, you know?

What about guys you've worked with outside of the band, like Paul Butterfield?

He's right up there, with Eric Clapton and Bob Dylan. Roger Waters, Ringo Starr, Stephen Stills, Neil Young. I mean, the list is endless.

Is there anybody you didn't play with that you always wish you had hooked up with?

Liberace [laughs]. Listen, I don't mean to drop any names, but I'll tell you a true story: They made this movie, Myra Breckenridge. Keith Moon was my neighbor in Malibu, and Ringo had a house in the Hollywood Hills, and we're having this party at Ringo's house. It had something to do with Myra Breckenridge, because Mae West was there! I was kind of in a corner with Joni Mitchell and Alice Cooper and Neil Young. And there was this guy who was standing there, a big Rick Danko fan, and he was saying, "Rick, if you had a wish, who would you like to meet?" I said, "I'd love to meet Mae West." He said, "I brought her!"

You got your wish!

Yeah. She was sitting in this other room on . . . it wasn't a pedestal, but it was like a raised chair or something. And she's making these old-people noises. [Danko illustrates with quivering sighs.] Well, he grabs me by the elbow and takes me over. He's yelling at the top of his lungs, "This is Rick Danko! He's a great singer! He's a great bass player!" It was an embarrassment! She sticks out her hand and goes [more biddy-like sighing]. So I grabbed her by the hand and I said, very shyly, "What are you doing next Tuesday night?" And the guy yells at me, "Ya gotta speak up! She's hard of hearing!" [Laughs.]

Have you heard her record of "Twist and Shout"?

No, but she sure could sing. She was great.

Wreck on the Highway

You had a car accident in 1968 that led to long-term physical problems.Yeah, I broke my neck and back in about nine places. What happened was, I really kept it hushed, because I didn't want everybody saying, "How do you feel?"

What actually happened?

I ran into a cloud on top of a mountain, and my windshield didn't wipe. It was the first time I was ever unconscious. But I got up, I walked away from it. Once I lay down, of course, that was the end of it, until I healed. But the thing was, I didn't let that get out, publicity-wise, and the Band went from no money to 60 grand a night, just because we weren't available. They always want what they cannot have.

Your injuries must have affected your musical performance.

I'm sure they did. I'm sure it affected everybody [in the group]. But we're still here; that's what's important.

Issues in Songwriting

A new generation got to know your music a few years ago when Absolutely Fabulous went on the air with "This Wheel's on Fire" as its theme song.Yeah, that was great. I saw it. And I got two checks for over $100,000 -- checks from God, we call that. At the time, I likely needed the money. So I was thankful.

There are other issues related to songwriting, in disputes you've had with Robbie Robertson over sharing credit for much of the Band's repertoire.

I don't have a problem with any of it, you know? I'm a very thankful person. Whatever publishing I've shared with people, whatever songwriting credits I've shared and whatever payments I've gotten, I'm thankful. I could have ended up having to get a real job. I'm thankful for what the Band has represented and what the Band has done. I'm not gonna sit here and tear the Band apart.

Is there any chance that you and Robbie would work together again?

Ah, I think that to deal with the past, we would have to deal with the future. And that's enough said.

Because who knows what the future will bring?

That's right.

Last Album, Lost Future

![[Live on Breeze Hill]](../band_pictures/live_on_breeze_hill_viney.jpg)

|

Yeah. This guy threw a party, and he wanted me to put together a great horn section. When I found out that he was serving rack of lamb from Australia, and he was serving lobster sandwiches, and nobody was getting married, and he gave me a $20,000 budget for a horn section, I was like,"Wow, let's record this." I think we did a pretty good job.

Your vocal range has changed over the years. Have you lowered keys on a lot of songs?

Yeah. You know, I'm getting older, and I've dropped the keys. The first half of my life, I was singing songs that were too high for me to sing, and I enjoyed them less. Now, from my acoustical performances, I've dropped everything down about a whole key, and I enjoy it more.

Does that change the feel of the songs?

Yeah, but I can live with it. I can do what I'm supposed to do.

What's in the future for you at this point?

I'm making music, you know? I've got three different record projects that I'm working on right now. I'm a founding member of a new record company. You know, Greenpeace is my payback: I donate certain portions of my proceeds to Greenpeace. Hopefully we can educate the world to pay a little more attention to global warming.

How did you come to embrace this agenda?

Well, I used to work with the Dolphin Project. It's like Pete Seeger says: If you don't point people in the right direction to focus on their problems, they will never get solved. It's like Lake Erie is on an upswing about being cleaned up; I never thought I'd see that in my lifetime. Same with the Hudson River. But we've got to do something about the rainforests, we've got to do something about global warming. It's gonna take corporate sponsorship, it's gonna take money for research, it's gonna take all of the above. One of my pet projects is helping to move people in the right direction.